i have friends, i definitely have friends

navigating adult friendship and learning how to be alone

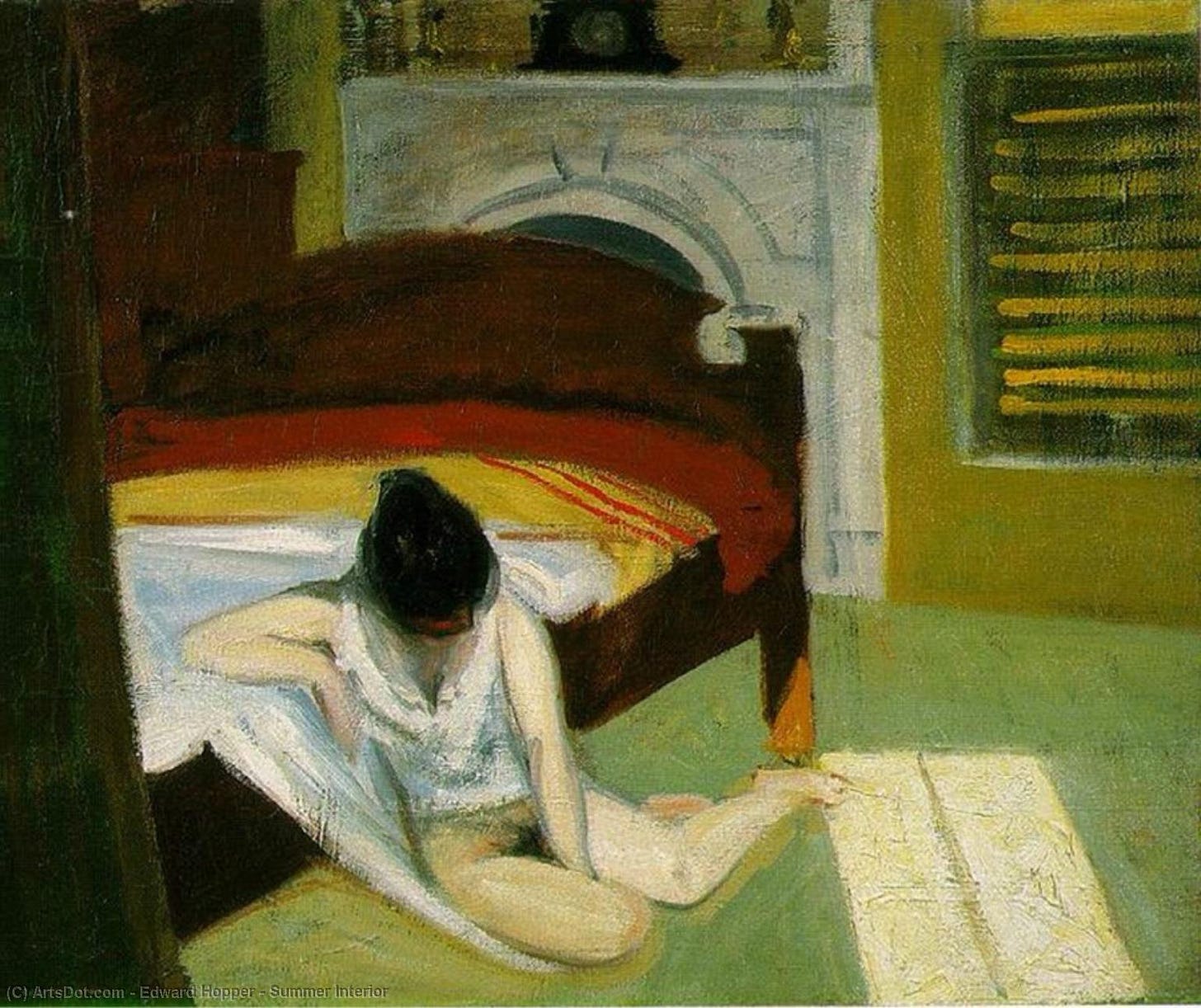

The last time I was in the flat by myself all evening, I had good intentions. I wanted to cook something special, burn incense, finish a new essay on here, maybe even dig out the first draft of my novel and try not to viscerally hate it. At 6pm I ran myself a bath, which I usually like, but it felt strange and vulnerable when I was the only person in the flat, lying naked in a broth of diluted soap and my own grime. There was a shadow of black mould on the bath sealant a few inches away from my nose which was probably creeping into my lungs, wet and indelible on their pink lining. My brain felt stagnant, a pond craving the splash of a pebble, begging for ripples and waves. I wasn’t entirely sure I had physical borders, that I didn’t blur at the edges, that I wasn’t escaping through a gap in myself.

After my bath, I watched four episodes of Baby Reindeer back-to-back on the sofa while chain-eating Ryvita crackers. I panicked that AI was going to destroy the world, and read some articles that said it maybe would. I found a mole I hadn’t noticed before above my collarbone and spent forty minutes on various forums trying to find some confirmation it wasn’t skin cancer. I picked at a cuticle until it bled. Rosa came home and asked what I’d been up to; this and that, I said. The Verywell Health page about melanomas was still up on my laptop. I couldn’t answer her honestly. I couldn’t say, oh, I was deflating, imploding, ceasing to exist in any meaningful sense because no-one was looking at me.

Ten years ago I would have relished the prospect of an evening alone in the house, because back then it allowed for uninterrupted, indulgent, delicious time on the computer, which meant hours flipping between Tumblr, YouTube, and a 50k-words-long Les Mis fanfic. It was a safer solitude than the one waiting for me at school the next day, because no-one was there to witness it, it was secret. At school, I walked around apparently with a huge neon sign above my head telling everyone else I was neurodivergent and queer before I even knew myself. It had been there since I was six or seven. I didn’t have the words to explain or understand why I was an easy target, so all I knew was there was something different about me, something very wrong.

If you have ever been a lonely child, part of you stays her forever. A void opens up inside you when you are very small and then mocks you all your life for being unable to fill it. No number of friends or strength of love can fill it; the well is bottomless. In The Lonely City, Olivia Laing describes her own loneliness as “an infant’s wail: I don’t want to be alone. I want someone to want me. I’m lonely. I’m scared.” When I am confronted with even a few hours alone, my own infant starts crying, echoing up from the depths of me: We’re still here! I was right! There is something wrong with us!

The Lonely City tells the stories of some of New York’s most influential artists and their respective lonelinesses, but it’s also about Laing’s own solitude in the city, after the end of the relationship which brought her there. She suggests that loneliness begets itself; the more alone you are, the more solipsistic your world, the less able you are to confidently interact with others, forge new relationships, end the cycle. Laing is ashamed at her own isolation, sensing the judgement of onlookers, their assumptions that there must be something wrong and strange about her for failing to do this most human of things. “My life felt empty and unreal and I was embarrassed about its thinness, the way one might be embarrassed about wearing a stained or threadbare piece of clothing,” she writes.

I have felt the same. I’m extremely willing to over-share about my depressive episodes, past relationships, even my intense bouts of hypochondria, but the idea of disclosing that in the past I didn’t have many friends, and sometimes I still feel lonely, makes me wince. Maybe it’s because I know that others, in turn, would be reluctant to admit they relate. Or because it seems too small and sad to be funny, so any joke about it would seem like I wanted pity. Thinking about it, I would then get the urge to say, but of course, I have friends now, and that would come off hollow, too. I’d have already seeded the thought that perhaps I do not have the full, rich, exuberant life that is assumed to carry on in the background of everyone we know, and a cold awkwardness would descend, like mist. It would feel too vulnerable, like even bringing it up would be getting too close, asking too much.

I know I’m only clarifying this to fulfil that urge, but yes, I do have friends now. I have some very old friends from childhood, a small core group from university who I’m still individually close to, and then quite a few other, one-on-one friendships, again from uni, or work. I’m funnier and chattier one-on-one, I know that about myself now.

What I also have, though, is a tendency to think about my friendships like I’m about to be audited for evidence that I have them. In past years, I’ve typed out lists of them in my Notes app, to reassure myself that they exist. I’ve felt like Rebecca from Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, in Season One when she’s trying to organise a house party in a city where she knows no-one, all to impress a boy, singing a peppy, crazed duet with her nine-year-old self. I have friends, I definitely have friends. Nobody can say that I do not have friends. The list of friends that ensues dwindles quickly, and by the end features grocery store staff she doesn’t know by name, but is delivered with the same manic fervour from start to finish. As the audience, we sense that no matter how long that list was, no matter how real those friendships, it wouldn’t be enough to truly convince adult Rebecca or her younger self that she really does have friends.

I think a lot of my discomfort at the moment comes from adjusting to how friendships work when you’re in your twenties. At university you get to see everyone at their most raw and tumultuous, the pure malleable yolk of themselves, in bed with a hangover or dancing in their pyjamas or crying so violently the world cracks open. Now that I live in a city away from a lot of my friends, and only get to see some of them every few months, I yearn for that unabashed closeness, that proximity again. Post-graduation, when we’re no longer living together, social events with a lot of our friends are relegated to cafes and restaurants and pubs, impersonal third spaces, so we only get to see the people our friends are when they are in cafes and restaurants and pubs. And when we are all together at someone’s house, that person is hosting, and we are all guests, and so adult formalities begin to creep in. Everyone’s borders are hardening.

Reaching twenty-four has felt unsettling, because my memory of myself now stretches back further than I can see. It is like the point at which, wading deeper into a lake, the water becomes murky enough that you cannot quite see your feet. I am no longer new to the world; if this were a coming-of-age film, the credits would be rolling by now. But even now, I can’t quite accept that I get to love, and to be loved, by people who feel like home. That I am still loved, even if I haven’t seen someone in a couple of months, or if the shape of our friendship is changing. I still have a distinct sense that my childhood loneliness was actually my default, that anything else since has been a fluke, and will one day come to an end. I can’t quite accept what I deserve - what we all deserve.

Hi guys,

So this one was vulnerable!!!

Thank you for the love on my last piece - it gave me the confidence to write this one.

Ellie xx

This is stunning writing. There was a period of about 10 years where I just retreated into myself, total loner. The Lonely City and your line "If you have ever been a lonely child, part of you stays her forever" hit like a sledgehammer. I think learning to make friends is a lot like learning a language--there is a period of time where we are primed to acquire those skills. If the period is missed, you can still learn how to do it but you will never be as fluent as a "native speaker." Thank you, Eleanor, for this powerful work

i deeply resonated with the contrast between how you get to see your friends in their rawest states vs at impersonal third spaces. i can even argue that being perceived on the context of the latter creates a sort of ambivalence - you get to envelop yourself in a guarded bubble of the persona you want to project, but said bubble prevents you from really making any sort of real connection, furthering that loneliness even more.

just wanted to share a thought that popped up as i read this lovely piece. :)