If you were growing up as a lonely teenager at the same time as me, you might have come across the now-infamous Tumblr blog Your Fave Is Problematic. It described itself simply as “Problematic shit your favorite celebrities have done”; each post was a long, bulletpoint list, detailing the wrongdoings of a particular celebrity, with sources linked. The blog is still up, though now years-defunct; you can still access an alphabetised list of everyone who had a post on there. It’s a now-amusingly-dated group - Misha Collins features, as does Lena Dunham, Laci Greene, and Benedict Cumberbatch.

The offences on these lists were various, and lumped indiscriminately together regardless of perceived severity. One of its longer posts was about Jennifer Lawrence, recording her referring to Katniss as “white trash” and disrespecting the cultural importance of a particular rock formation to Indigenous people in Hawaii, but then also her apparently saying “Oh, I can't stand shy people. Like, make it up already.” At the time, Lawrence was at the peak of cultivating her image as the relatable quirky girl, falling on the stairs at awards ceremonies, appearing in that infamous Oscars selfie, declaring her love for pizza in interviews. That is to say, she was trying to seem just like us, trying quite hard to be liked. Eleven years on, I still remember coming across the YFIP post on Lawrence and feeling betrayed, in a way that seems ridiculous and humiliating in retrospect. But I was thirteen years old, low on both calorie intake and critical thinking skills, so it was actively nice to hear an actress talk about how much she enjoyed food. After seeing the post, I experienced for the first time that particular feeling of disappointment you get when a celebrity or public figure turns out not to be quite who you thought they were.

On the YFIP Tumblr, there was also a page called ‘Now What?’, for people who had just stumbled on an entry about their own favourite celebrity:

Am I still allowed to like them?

Yes. No one is stopping you from doing anything. You can like and consume their work without liking them as a person. You can even like them as a person, so long as you recognize that they do have problematic issues.

How can I be a conscious fan?

Recognize that they did something wrong. Accept it. Don’t try to defend it or explain it. Say “so-and-so makes great music, but I wish they weren’t racist” or “I think that they’re really talented, but they are also sexist”. It’s a package deal. Tell other fans what they did. When praising them, don’t ignore the problematic stuff. Talk about that too.

Only around half the people in the original Oscars selfie have made it through the last decade without some kind of allegation surfacing: Kevin Spacey is right in the centre, Brad Pitt to his right, half of Jared Leto’s face at the very edge, Ellen DeGeneres front and centre. I saw someone point out recently that if it were taken today, it probably wouldn’t have garnered much attention online at all, let alone made international news. If it did, it would instantly have been dubbed cringe, or a publicity ploy (which it was, incidentally, for Samsung). Lots of us know better, now, than to place blind faith in exceedingly wealthy people we do not know, simply because they are attractive, funny, and sometimes make good art, or entertaining films.

The answer given on Your Fave Is Problematic’s What Now page, on being a ‘conscious fan’ - ‘When praising them, don’t ignore the problematic stuff. Talk about that too’ - is advice many of us follow instinctively now. But at the same time, it would be unfeasible for a blog like Your Fave Is Problematic to exist today without being laughed off the Internet. The ‘problematic stuff’ discussed in many TikTok comments sections now isn’t necessarily racism, or cultural appropriation, misogynistic or transphobic comments; sometimes it’s artists reminding us of concert etiquette, or saying no to photos in the street, or sometimes just that an artist’s ‘vibes are off’. And on the flipside, I wonder if the blog has, perversely, helped to create a ‘problematic fave’ ideal; whether ‘problematicness’ has become a way for some people to develop a different kind of self-image post-cancellation, or to pursue their fame in the first place.

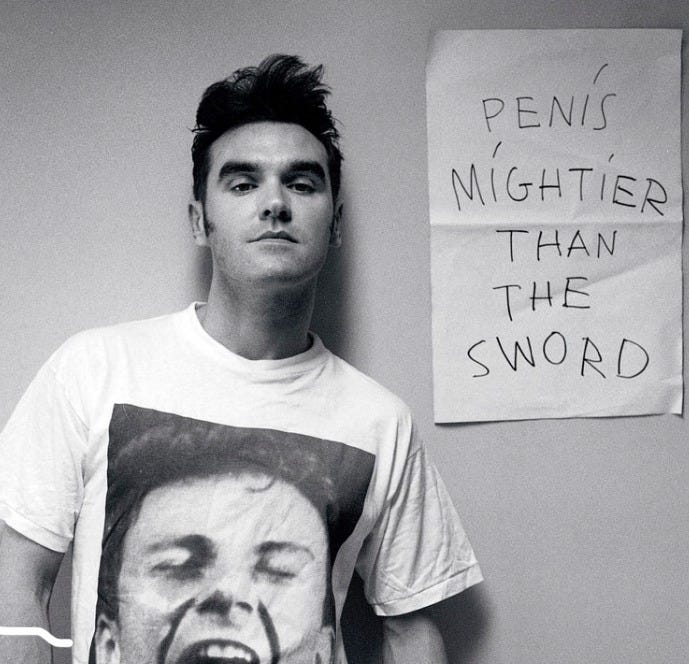

Problematic-favedom isn’t an entirely new phenomenon; I think Smiths lead singer turned embarrassment-to-Britain, Morrissey, might have been one of its original archetypes. Awareness of his racism and fascist leanings has increased steadily; now most newspaper features on him focus around it, and appear to see no way for him to make a public comeback. When we talk about Morrissey’s public image turning sour, we often rattle off a YFIP-style list of evidence from the late 80s and early 90s, like an itemised timeline of his downfall. Like in 1992, when he came out on stage as Madness’ support act, draped in a Union Jack; the racist lyrics in ‘Bengali in Platforms’ from Viva Hate, or the far-right sympathies in ‘The National Front Disco’ from Your Arsenal. We envisage a steady process of radicalisation; we talk about his betrayal of the fans, what a shame it all is; we rarely consider the possibility that he was, more or less, who he is now from the very beginning.

In 1986, when The Smiths were in their prime, the band came out with the single ‘Panic’, which takes aim at contemporary British popular music: ‘Burn down the disco / Hang the blessed DJ / Because the music that they constantly play / It says nothing to me about my life,’ and then ending with the refrain ‘Hang the DJ, Hang the DJ.’ The lyrics received minor backlash, with accusations made against the band of inciting racism or violence against Black DJs, musicians, and artists. Both Morrissey and Johnny Marr claimed that the idea for the song came from BBC Radio 1 announcing the news of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, and then, straight after, playing I’m Your Man by ‘Wham!’. But in a Melody Maker feature that same year, where interviewer Frank Owen attempted to get to the bottom of the racism allegations, Morrissey did little to put any confidence in his and Marr’s story, instead calling reggae an “absolute total glorification of black supremacy”, and commenting that “to get on Top Of The Pops these days, one has to be, by law, black.” But The Smiths’ success and reputation as counter-cultural icons obscured this, at the time. The legions of miserable teenagers who adored them, and chanted Hang the DJ along with them at gigs, either were too ignorant to put two and two together, thought Morrissey was joking, or simply didn’t care.

“For years,” writes Dr. Chris Allen, “I genuinely believed that Morrissey was either being misrepresented or just ironic. When Morrissey claimed reggae music was ‘vile’ in his Smiths heyday, I put it down to him trying to provoke a bland 80s music press out of its slumber.” There is a double-think to what is going on here, to hearing objective racism but assuming it’s all merely in jest, or parody, or some kind of intelligent social commentary; a double-think that is a mark of white privilege, that relies on none of it feeling personal to you. In an article for the Quietus, ‘Why It’s Time to Ditch Your Morrissey-Loving Friend,’ David Stubbs mentions being married to a Sikh woman in the early 1990s, whose brother was, originally, a big fan of the Smiths:

… her brother, Gurbir Thethy, adored The Smiths, subversively basing his dance at Sikh weddings on that of Morrissey. As someone who had been chased through the streets of Birmingham for not being white, Thethy identified with Morrissey’s sense of being an outsider, both domestically and in society at large… ‘Bengali In Platforms’ was like a kick in the teeth from a man he had idolised; the scales fell from his eyes.

"What I didn’t think was that his (sometimes uninformed) literary allusions were a mask for his sense of elitism," says Thethy. "And that suddenly became writ large with ‘Bengali In Platforms” In 1988 I was 21 and overt racism was still the order of the day. The National Front was gone but only to be replaced by the BNP – and then this song happens. I felt betrayed. I felt like all the white boys I’d ever been "friends" with had only ever been a tolerance – that what they all really thought about me was summed up in this song. I was hurt beyond words.”

I think when people say Morrissey ‘became problematic’, they mean when predominantly white listeners stopped pretending, or actively believing, that he was joking. There had been press whisperings about his political leanings from the early 1990s. But a public consensus that he was now on the extreme far right only came in more recent years, by which time he had started to seem a lot more like someone’s estranged, drunk uncle at a family reunion, muttering hatefully in the corner; when he was no longer the rail-thin, androgynous, ambiently queer young man with gladioli in his back pockets, and instead, a lot more like how most white audiences would imagine a racist.

There’s been humorous speculation online that Matty Healy has taken up Morrissey’s cultural mantle. Earlier in his career, Healy appeared outwardly left-wing, speaking out at The 1975’s concerts about abortion bans, even tweeting angrily at the Tory government in 2016. But recently this has been replaced entirely with a string of unfortunate interview quotes and celebrity allegiances; his racist comments about Ice Spice, the admission that he watches pornography that violently degrades Black women, his associations with Adam Friedland, Dasha Nekrasova and Anna Khachiyan, his use of the R-slur.

More so than Morrissey, though, his performance as problematic fave is conscious; he often makes reference to his own offensive-ness, and appears fixated on his cancellation(s). like in Being Funny in a Foreign Language’s ‘When We Are Together’: And it was poorly handled, the day we both got canceled / because I'm a racist and you're some kind of slag. And then in Part of the Band: I was living my best life, living with my parents / Way before the paying penance and verbal propellants / And my, my, my cancellations. If Your Fave is Problematic were around today, and made a post on him, he’d probably put it on his Instagram story; his old handle, @theproblemattic, was maybe even a riff on it. Is he halfway down a pipeline, or is it all for bizarre, tasteless show? In a way, that question is the show. And, at least for now, a lot of people are still watching.

The online literary sphere, too, has acquired its own problematic faves, or anti-faves. I’m thinking in particular of Honor Levy, the much-discoursed 26-year-old author of My First Book, a short-story collection which tackles cancel culture, identity politics, and the Internet. Some critics have lauded Levy as ‘the voice of Gen Z’; other reviews have wondered if the book was published too early, or dubbed Levy the Internet’s ‘shaman’ rather than its storyteller. But it was an unfortunately infuriating profile on her in The Cut which fuelled most of the backlash and negative buzz against Levy - and perhaps a lot of her book sales, too. (I’d never heard of someone hate-buying a book until Levy’s came out; I’m ashamed to say I hate-bought it, too.)

In the short story Cancel Me, she writes: “The men yelling at you on the street corner in Bushwick probably do not want to rape you.... Wearing your pink hat and marching against Trump is not going to do anyone any good except you. Awareness does not need to be raised.” But then - “I’m not asking you to agree with me. In fact, I’d be happier if you didn’t.” Cancel Me doesn’t really read like a story; some sections lapse into a series of statements, or provocations. It’s snappy and buzzy and compelling to read - but I’m not sure what reaction she wants from me, other than disagreement, I suppose. Of course fiction doesn’t require a cause, or a point, but the absence of one here strikes me, all the same.

In Pillow Angels, at the end of the collection, when the narrator tells us how her and her friends “all want to be Dachau-liberation day skinny for spring vacation on Little St. James” - what is Levy’s intention here? How does she want the reader feel? Shocked, disturbed, but what else? She makes that same comparison again in Shoebox World, whose male love interest “looked at photos of the camps being liberated for thinspo and couldn’t make it up a flight of stairs” in his youth. We’re supposed to find it ironic, I suppose, privileged teens with eating disorders aspiring to look like people who were imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps, tortured and starved. But mostly, I think we’re meant to flinch, recoil at the fact she brought up the Holocaust at all, and then keep reading. Levy’s sentences are short, repetitive, almost panicked, so you end up reading at a frenetic, thoughtless pace; there’s no time to think, the next sentence is here, and it’s about climate change. Half the time I’m not sure why she chose to include what she included in the final draft, aside from the fact that, among young, left-leaning people, it’s considered daring, offensive, even repulsive to write it.

There is an argument open to Levy, as there is (rightly) for all authors, that the views espoused in My First Book are not her own, that they are the narrators’. But most of her narrators are nameless women from a similar social background to Levy herself; they are, for the most part, all extremely online nihilists with self-professed wealth and privilege. If they aren’t meant to be fictionalised Levys, then she didn’t put much effort into othering them from herself. And the narrator trap is easier to fall into than you’d think. I’ve been guilty of making my protagonists the worst version of myself, their narration my cruellest inner monologue, because it’s not me, technically, it’s a character. It’s the mean, messy woman who has made literary fiction her home, but bubbles under the surface of all of us. If it was this ‘problematic’ other-self who brought me success, money, or fame, would I be able to stop myself from becoming her entirely? I don’t think so.

Both Rosa and I got a real, visceral reaction from the first page of the book; it felt wrong, on some instinctive level, for discourse this niche and toxic and inflammatory to have made it onto paper, for a book to feel like scrolling. And it does feel like scrolling, in that each quick-fire sentence is made to feel as important as the next; we’re not given any chance to breathe. It’s like flicking through Instagram Reels: whether what we’re watching is a woman dying of cancer, or a makeup routine to make your nose look smaller, or video footage of an active genocide, it’s all flattened to slip easily down the toxic, frothing stream of content. Everything seems to carry the same weight, everything is a ten-second clip, beamed to us on the same, small rectangle. I wonder whether this is why there is no Overton window online; why Instagram reels comments sections have become abusive hellscapes, and incel ideologies and language have entered the mainstream. Because you can hide your name and face, but also because nothing seems real anymore, nothing is off limits. And because online is now where and how we do much of our living, this has begun to bleed into the physical world, too, into works like My First Book, into formerly leftist influencers Instagramming their attendance at Trump rallies.

Perhaps the attention economy has created an elision between shocking art and good art, because shocks are all that jolt us out of dissociation, even for a second. Think about last year’s Saltburn, for example, which is, in essence, one shocking moment after another (bathtub scene! grave sex! his Dad isn’t really dead! ripping out Rosamund Pike’s breathing tube!) but, after all that, nothing really to say, a class satire with no message, let alone a clever one.

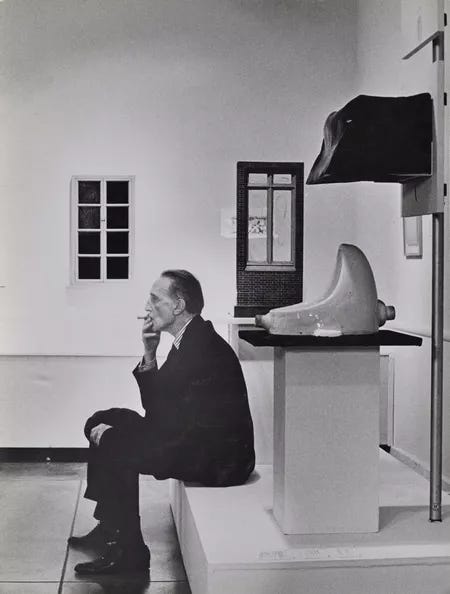

I’m not saying that shock itself is valueless. In 1917, when Marcel Duchamp presented a urinal to the Society of Independent Artists, signed it with a scrawled pseudonym and proclaimed it his “Fountain,” he wanted to shock. But he also wanted to ask the question - can we deem something so ordinary, so “ready made” as he put it, art? Can art be something you piss on? To be provocative, I think, you have to be provoking something. Otherwise you’re just making people raise their eyebrows, or say, wow, she really went there, without asking themselves whether there is a place worth going.

What of the creator of Your Fave is Problematic? In 2021, she identified herself as Liat Kaplan, and wrote a short piece for The New York Times about the blog, and her mental state while running it. Her sister had recently died in a rural hospital after a bus crash; she took time out of school to grieve, but the blog, and the work of unmasking celebrities for their wrongdoings, begun to consume her. “Who was I to lump together known misogynists with people who got tattoos in languages they didn’t speak?” she writes. “I just wanted to see someone face consequences; no one who’d hurt me ever had.”

Kaplan appears ashamed and regretful, both of her own actions on Your Fave is Problematic and of the strange, outsize cultural impact they’ve had, both as a precursor to MeToo, and as fuel for the still-raging right-wing backlash against ‘wokeism’. To her, the blog now seems like “vengeful public shaming”. “I was angered by hypocrisy and cruelty,” she says; “what I did about it was apply a level of scrutiny that left no room for error.”

I agree with her - but I wonder whether at the same time, we should take what people say at face value. I think we should listen beyond the irony. When Matty Healy sings, “Because I’m a racist,” what if we just believed him? Why are we so desperate not to? To me, art is about seeing the humanity in all of us; about knowing that each and every person you come across has a soul as heavy as yours. Art that rejects this, even in the interest of provocation or social satire, leaves me feeling cold and queasy. After all - in the words of Morrissey himself - it’s so easy to laugh, it’s so easy to hate. It takes strength to be gentle and kind.

What about art that's leaving the message unsaid so as to allow the audience to do the working out, reinforcing and making stronger the idea they draw from it?

Fantastic read.

I missed the essay by the "your fave is problematic" creator, but love how you framed your piece with it. I remember that blog's heyday so well. I'm not surprised to find out the creator was trying to find certainty and justice. That kind of tragedy has such a grip on the psyche. I've certainly gone through phases of being obsessed with justice followed by apathy and choices I regret that don't align with my values, and then beginning all over again. The challenge is returning to compassion and kindness.